Donald B. Wagner, Background to the Great Leap Forward in Iron and Steel

Click on any image to see it enlarged.

‘The Great Leap Forward in Iron and Steel’, 1958–60

| On the

campaign and the period see especially Roderick

MacFarquhar, The origins of the

Cultural Revolution,

vol. 2: The

Great Leap Forward,

Oxford 1983; Michael Schoenhals, Saltationalist

socialism: Mao Zedong and the Great Leap Forward

1958, Stockholm 1987;

—, ‘Yang Xianzhen’s Critique of the Great Leap

Forward’, Modern Asian

studies, 1992, 26.3:

591–608; S. A. Nikolayev & L. I. Molodtsova,

‘The present state of the Chinese iron and steel

industry’, Soviet geography:

Review and translation,

1960, 1.8: 55–71; R. Sewell, ‘A guide to the

Chinese steel industry’, The British

steelmaker, July 1960,

259–263; Robert R. Bowie

& John K. Fairbank, Communist China

1955–1959: Policy documents with analysis,

Cambridge, Mass., 1962; Harold C. Hinton, The People’s

Republic of China, 1949–1979, a documentary

survey, vol. 2: 1957–1965: The

Great Leap Forward and its aftermath,

Wilmington, Del. 1980. |

With the Communist assumption of power in 1949 came peace

after more than a decade of war and destruction. In its

first years the government was fully taken up with acute

problems: the rebuilding of agriculture and the most basic

infrastructure. Meanwhile the first steps were being

taken, with the help of the Soviet Union, toward the

establishment of modern industry – coal mines, steelworks,

oil refineries, and much more.

‘Gridlock’ problems gradually became apparent.

Development of China’s infrastructure (railroads,

highways, harbours, the electric power grid, etc.)

required steel in immense quantities, but production of

steel in the large-scale modern plants recommended by

Soviet advisers required a well-developed infrastructure.

Resources for investment in industry could only come from

agriculture, and in the Soviet Union under Stalin the

peasants’ surplus had been confiscated using hard methods.

But the Chinese peasants had very little surplus, and

furthermore Mao Zedong and most of his associates came

from peasant roots; they felt nothing like the hate and

contempt for the peasantry that had driven Stalin. Around

this time the political tension between China and the

Soviet Union began to show itself.

In response to this challenge the Planning Unit for

Ferrous Metallurgy under the Ministry of Metallurgical

Industry designed and built several ironworks with blast

furnaces of modern design but small size, typically 50–80

cubic metres. This is dimunitive compared to modern blast

furnaces of 1500–3000 cubic metres, but large compared

with the traditional blast furnaces – they were seldom

over 10 cubic metres, and for example in Dabieshan they

were around 0.4 cubic metres.

An engineering conference on the new small ironworks was

called in June 1957, and according to the final report the

participants were largely positive. Among the conclusions

was the following, on the choice of scale:

| Yejin bao,

1957.22: 18. |

In

the planning of a small blast furnace for a locality,

the scale of production should be set to satisfy local

needs; it should definitely not be nationally

oriented. Especially where the conditions for

transport of raw materials are not adequate, the scale

should not be too large. Many comrades proposed in

their contributions that the appropriate size for a

small blast furnace should be 30–50 cubic metres.

According to Comrade Tang Fumin, ‘preliminary analyses

and economic comparisons suggest that a planned blast

furnace of 80 cubic metres in a typical production

unit will require an investment of 25,000 yuan,

including the blast furnace itself and installation of

water, electric power, transportation, and facilities

for workers. A blast furnace of 50 cubic metres, on

the other hand, requires only 18,000 yuan, and

a blast furnace like those in Sichuan and Hunan, of

less than 30 cubic metres, requires about 13,000 yuan.

An industrial worker’s salary in this period was on the order of 50 yuan per month, so these investments were not at all small. The production units seem to have been plants with 20–30 workers, producing for a relatively large local market. The largest of the traditional blast furnace types, for example those in Sichuan and Hunan, could be used, but the emphasis was on larger and more modern plants. This was the strategy of the central government in early 1957, and even at a distance of 50 years it seems to have been appropriate for the conditions of the time.

In the provinces, however, there was still interest in

very small blast furnaces like the ones used in Dabieshan and Fujian. In isolated regions

this technology had never been forgotten, and it had begun

to thrive again after 1949. Obtaining iron and steel from

outside for local reconstruction required money and

political influence, both of which were in short supply in

the poorest regions. A continuation of the local iron

industry was perfectly natural. In the last months of 1958

a large number of brochures with technical descriptions of

the construction and operation of very small blast

furnaces were published by various provincial governments,

and these must have been under preparation from some time

in 1957. My description of the technology in Dabieshan is partly based

on one of these. The brochure states that an ironworks

which uses the technology it describes requires an

investment of ‘only’ several ten-thousands of yuan. Obviously this

refers to an industrial plant with numerous workers. At

this time no one was suggesting that the peasants should

go out and make iron in their backyards.

Some very large problems were ignored here. Most of the smallest blast furnaces were fuelled with charcoal, and increasing their production would necessarily lead to environmental destruction. And those which used mineral coal most often produced cast iron with a high sulphur content; this could be used in foundries, but it could not be converted to useable wrought iron or steel.

Politics now took an unfortunate turn. The happy days

that followed the revolution of 1949 gradually receded,

and criticism of the Communist Party by intellectuals

became strident. In 1957 the party responded with the

‘Anti-Rightist Campaign’, which in large part was a

campaign against experts. Engineers and economists who

warned against predictable consequences of some of the

party’s dispositions were demoted or fired; the last

bastions against ignorance or even stupidity fell.

Enthusiasm took command.

| Peking Review,

4 March, p. 8; 8 July, p. 8; 29 July, p. 12; 2

September, pp. 4, 6–7; 16 September, pp. 21–23;

30 September, pp. 13–15; 14 October, pp. 15–16;

21 October, pp. 3–4; 11 November, pp. 14–16; 18

November, p. 3; 30 December, pp. 6–9. |

Freed from the warnings of experts, the government’s

ambitions rocketed, as can be seen in the official

magazine Peking review

for the year 1958. The national economic plan for 1958

included the construction of 14 small and medium-sized

‘metallurgical projects’, to be administered by local

authorities. In April the Great Leap Forward was

announced: collectivization (the formation of communes

rather than cooperatives) was to be encouraged, and 13,000

small steelworks were to be established, mostly to be

administered by the new people’s communes. These were to

have a capacity of 20,000,000 tons, i.e. an average of

about 1,500 tons per year, so what was meant seems to be

small modern plants plus perhaps the largest of the

traditional works. The photographs directly below probably

show furnaces built at this time.

By the end of July 50,000 small steelworks were said to

have been built, in August 240,000, and in the middle of

September 350,000. Most of these no doubt used very small

traditional blast furnaces like those of Dabieshan and

Fujian. How many actually produced anything significant is

not clear.

|

| Model people’s commune, propaganda poster from the Great Leap Forward, 1958. At the top right are three blast furnaces. To the left of these, a fertilizer factory and a cement factory. Centre right, a research field, including scientist (with magnifying glass), lecturer, and a busfull of interested persons from other communes. Top left, fields of grain and cotton. Left centre, granaries. Further forward, hospital and collective dining hall. Bottom left, retirement home. (International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam, http://www.iisg.nl). |

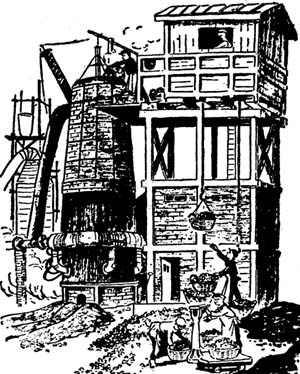

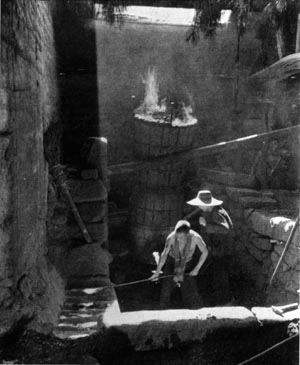

A directive of 29 August announced the forced collectivization of all agriculture. The poster on the left shows the ideal, including a collective dining hall and three blast furnaces. Each of these is labelled ‘blast furnace’, and they are more or less correct renditions of one of the traditional blast furnace types (see the photograph below), but there is no blast apparatus and no arrangement for charging, and the workers seem to be taken from a photograph of a modern Siemens-Martin open-hearth steelmaking furnace.

|

| Blast furnace in Wushan, Gansu, 1958. (Photo Rewi Alley; archives of the Needham Research Institute, Cambridge). |

|

| Blast furnace in Jinzhai county, Anhui, photographed 1958. (All China makes iron and steel, Peking 1959). |

In September 1958 Mao Zedong visited a small traditional

steelworks in Anhui and was greatly impressed. This was no

doubt a plant of the Dabieshan

type, as shown here on the right. The blast furnace looks

simple, like something anyone could build and operate, and

in a newspaper interview he called for a mass campaign for

steel production. Ambition now reached new heights:

everyone – everyone

– should go out and produce iron and steel.

The propaganda magazines of the time were very

enthusiastic about the mass campaign, but the photographs

which accompanied the glowing reports tell a different

story. Anyone who was convinced by the two photographs

below must truly have been a true believer.

The underlying problem was that the small traditional blast furnaces were not in fact at all simple. Efficient operation required a feeling for sounds, smells, and colours which could only be acquired through a long apprenticeship. Experience in blast furnace operation was available only in places where production had never stopped, and these were in the poorest and most isolated regions of China. We know very little about what went on here, for these regions were avoided by both journalists and politicians.

| Rewi Alley, China’s hinterland – in the Leap Forward, Peking: New World Press, 1961. |

The exception was the New Zealand journalist Rewi Alley,

a true poverty-romantic who loved the hardships and

dangers of travel in the poorest parts of China. He seems

to be the only journalist – Chinese or foreign – who saw

traditional ironworks actually in operation during the

Great Leap Forward. He remarked proudly that it was the

poorest peasants who made the best steel, and he no doubt

believed that there were moral reasons for this, but

economic factors surely played an important role as well.

The poorest peasants were the most isolated, and therefore

those who had never stopped producing iron by traditional

methods – their comparative

advantage lay in iron production.

The problems can be seen fairly clearly in an otherwise

optimistic report at the beginning of December:

| Peking review, 2

December 1958, p. 7. |

The

relationship between popularization and elevation –

two aspects of the mass movement – is well illustrated

by the nationwide drive to produce iron by native

methods. At the start, when the masses had not yet

mastered the necessary technical knowledge and the

resources of iron ore were not known in detail,the

accent was on technique and the quantity of output.

That was the period of popularization. Now, more

than two months later, a huge number of workers are

familiar with the preliminary smelting technique, the

distribution of iron resources are better known and

the output has attained considerable proportions. The

time has ripened for elevation. The small and

native-style furnaces will, therefore, be gradually

led to form integrated iron and steel centres using

both native and foreign production methods. When this

is accomplished throughout the country, the movement

will be elevated to a higher stage.

It can be seen between the lines that the mass campaign

had been no sort of success. Now it was necessary to drop

the campaign while preserving appearances: the mass

campaign’s only purpose had been to ‘popularize’ iron

production, not actually produce anything.

| Peking review, 30

December 1958, pp. 6–8. |

A report at the end of the year from the State Economic

Commission tells more. Among the tasks for 1959 are the

consolidation of the small iron- and steel-production

units, and ‘manpower should be rationally arranged and

used’. The steelworks should integrate traditional and

modern methods, as has been done in Shangcheng and Macheng

Counties (both in the Dabieshan

region). Transport must be improved, so that the plants

can obtain the necessary raw materials and the pig iron

produced can be delivered on schedule to the larger

steelworks.

Four furnace types

In virtually everything that has been written about the

Great Leap in recent years, both academics and journalists

have hopelessly confused four different technologies:

- The small modern steelworks designed and promoted by

the Ministry of Metallurgical Industry. They were – and

are still – a valuable supplement to the large-scale

plants which were built with Soviet help. But the

decision in April 1958 to build an enormous number –

13,000 – of such works was undoubtedly a grave error,

and it is uncertain how many of these were actually

finished, or produced anything much.

- The largest of the traditional blast furnaces. In

regions where the technology was well known, such as Sichuan and Hunan, they

contributed to production both by supplying local needs

and by delivering pig iron to the larger steelworks.

- The very small traditional blast furnaces which were

documented and promoted by various provincial

governments in east China. These could no doubt supply

local needs, and some seem also to have delivered pig

iron to the modern plants, but with a danger of

widespread forest destruction. Their operation was

probably best in poor and isolated regions, and

transport from these to markets or other works must have

been difficult. We hear of large quantities of ‘useless’

iron produced in these furnaces which many years later

lay rusting; in all probability it lay unused more

because of transport difficulties than of inferior

quality.

- ‘Furnaces of the masses’ – the millions of small blast

furnaces which Mao Zedong on 29 September 1958 urged the

peasants to build. The campaign was a massive failure,

but it lasted only a couple of months.

| Yejin bao, 1958.52:

33–35 + 30. |

A technical article published in December 1958 surveys

production costs in a sample of 104 small ironworks in 12

provinces and municipalities. The average cost of one ton

of pig iron was 250 yuan,

with considerable variation, from 108 yuan at one works in

Shanxi to 852 yuan

at one in Liaoning. The article goes on to explain the

discrepancy under four heads: (1) regularity of blast

furnace operation: (2) political leadership, mobilization

of the masses, and technical advance (i.e. efficient use

of labour and fuel); (3) transportation costs; and (4)

management costs. It is concerned only with serious

ironworks which used traditional technology; the ‘furnaces

of the masses’ are never even mentioned. The survey found

that ‘management costs’, which in other contexts might

have been called the profits of the owner, varied between

5.3 and 30.2 percent of total cost.

Unfortunately, historians who have dealt with this period

seem virtually all to believe that the ‘furnaces of the

masses’ were the only type of furnace involved in the

Great Leap. Serious consideration of the technology would

without doubt lead to a better understanding of the

politics and economics of the time.

An example: Fenghuangwo

An

article

in the propaganda magazine China reconstructs for December

1959 reports on a small steelworks in the people’s commune

Fenghuangwo in Macheng County, Hubei (in Dabieshan). The peasants of

the commune, responding to the appeal in April 1958 for a

great leap forward, had built several hundred blast

furnaces of a traditional type which was well known here.

These produced 700 tons of pig iron and 100 tons of steel

(undoubtedly the low-carbon steel which is generally

called wrought iron).

By the end of the year, as has been noted above, it became

clear that there were problems with the small traditional

ironworks, and the government recommended that larger and

more modern works should be built on the basis of

experience with the traditional ones. The small modern

steelworks at Fenghuangwo went into operation in November

1958, still producing pig iron in small traditional blast

furnaces of 0.4 cubic metres, but with more modern

Bessemer converters and rolling mills to process it. This

was probably an excellent arrangement, at least in the

short run, but the use of charcoal in the blast furnaces

would either have limited production or threatened

environmental destruction. Toward the end of 1959 most of

the traditional blast furnaces had been replaced by very

small modern blast furnaces of 3 cubic metres, presumably

coke-fuelled. The reason for the use of modern blast

furnaces of such small size was perhaps that the ore was

ironsand, which can be difficult to use in larger furnaces

– though it is also quite possible that this ‘3’ is a

typographical error for (for example) ‘30’.

The article presents the Fenghuangwo steelworks as a

great success. One would hardly expect any other

evaluation in this context, but it seems reasonable to

believe in the success. Dabieshan had always been a region

whose comparative

advantage lay in iron production, and the technical

details in the report are clear enough to allow the

presumption that the works produced quite good steel for

local consumption.

| Communist China

1955–1959: Policy documents with analysis, cited

above, pp. 540–550;

also The

People’s Republic of China 1949–1979,

cited above, pp. 762–769. |

| Daniel

Houser, et al., ‘Three

parts natural, seven parts man-made: Bayesian

analysis of China's Great Leap Forward

demographic disaster’, Journal of

Economic Behavior & Organization,

69.2: 148-159 . |

Click

on any image to see it enlarged.