Click on any image to see it enlarged.

The traditional iron industry in Sichuan

The southwestern province of Sichuan was in pre-modern times

quite

isolated from the rest of China. It communicated with eastern China via

the Yangzi River through a series of dangerous gorges (which since 2003

have been flooded by an enormous dam), and with Shaanxi via a famously

arduous mountain road. On the other hand transport conditions within

the

province were good. The name means ‘four rivers’, and transport on

these rivers bound the province together to form an economic whole. The

soil is fertile and the climate reliable, and these factors have made

Sichuan one of China’s breadbaskets. The province has attracted

immigrants throughout Chinese history, and its population density is

extreme. In 1997 Sichuan was divided into two, Sichuan and Chongqing;

see the map.

One consequence of these geographic factors is that the

iron industry has had good market conditions: demand from a large

population, with excellent transport, and isolation from outside

competition. There has been considerable production of iron since

ancient times, and in recent centuries the traditional blast furnaces

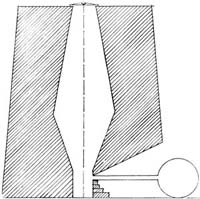

used in Sichuan have been the largest in China. The images on the left

show some of these.

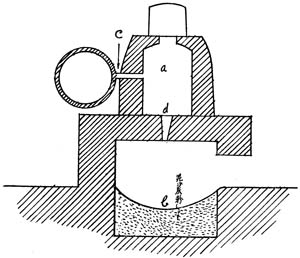

Conversion to wrought iron is done in a puddling hearth like

that shown above on the right. It resembles the simpler fining hearth used in Dabieshan, with the

difference that the fuel and the iron are separated. The fuel, either

charcoal or mineral coal, burns in the firebox. Air is pumped in, and

the flame proceeds downward and melts the iron in the puddling bed. The

puddler stirs (‘puddles’) the molten iron until the carbon is burnt out

of it and it can be removed as a pasty lump of wrought iron. The

separation of the fuel from the iron simplified the work and made it

possible to use mineral coal as the fuel without adding too much

sulphur to the iron.

It became necessary to adapt the technology to the new

economic conditions. The use of water power became uncommon, and the

blast furnaces were more often driven by manpower. This reduced capital

costs, not only because the blast apparatus was simpler, but also

because of an extra degree of freedom in the location of an

ironworks: it was no longer necessary to place the works on an

expensive site with access to water power.

The use of a limestone flux in the blast furnace also became

uncommon. An increased production of cement in these years had made

limestone more expensive, and another reason was that the blast furnace

could function longer without limestone. Limestone made the slag

alkaline, so that it attacked the furnace shaft, which normally was of

sandstone and therefore acid. It may be that the omission brought a

reduction in the quality of the iron, since limestone removes sulphur

as well as making the slag less viscous.

| On Sichuan during World War II, see Barbara W. Tuchman, Stilwell and the American experience in China, 1911-45, New York 1970 (many later reprints, some with altered title, Sand against the wind). |

In 1938, after the Japanese occupation of eastern

China, the Chinese government under Chiang Kai-shek relocated to

Sichuan and established its capital in Chongqing. The province was now

again isolated, and the entire civilian demand for iron could only be

supplied by the traditional industry. A great deal of experimental work

was done to improve the traditional technology using modern scientific

knowledge; the experiments continued after the war and up through the

1950’s,

seemingly with some success. The positive results of these experiments

may have contributed to the optimistic approach to the traditional

technology which characterized the period of the Great Leap Forward,

1958–60.

Click on any image to see it enlarged.