Click

on

any

image

to

see

it

enlarged.

China, 1600–2010

| On the history of the period

see especially Jonathan Spence, The search for modern China,

London: Hutchinson, 1990. One of many useful on-line sources is the Library of Congress

Country Study: China. |

China in the 17th century suffered from peasant revolts and

nomad invasions, resulting finally in the fall of the reigning Ming

dynasty. History books give 1644 as the beginning of the new Qing

dynasty, but in fact its consolidation took many years.

The 18th century was a period of peace and economic advance.

Especially the improvement of canals and roads led to a great increase

in inter-regional commerce and regional specialization. But then things

started going wrong. Traditional Chinese historical writing stresses a

‘dynastic cycle’, in which a reigning dynasty starts well and gradually

degenerates, so that after two or three centuries it falls and is

replaced by the next. This idea makes a certain amount of sense –

consider some of the developments that can accompany peace under a

strong central power:

luxury, corruption, population increase, increased commerce, and the

rise of local economic power centres in uncontrollable hands. But in

the 19th century a great deal of the dynasty’s problems came from

outside – from the West.

Spanish and Portuguese traders began showing up around 1600,

followed by Dutch and English somewhat later. The English East India

Company developed a major trade with China in the latter half of the

18th century.

The most important commodity in this trade was tea from China,

though there was also a considerable demand in Europe for silk and

porcelain. In the early years of the trade there was very little demand

in China for Western products, so the Chinese products were bought with

silver. Here lay the beginning of the Qing dynasty’s problems: mines in

the Spanish colonies in America brought a flood of silver to Europe;

great quantities came to China in exchange for tea; all this silver

caused inflation in China, and the country’s economy became unbalanced.

Chinese investors put their capital into tea production and other

activities related to foreign trade, to

the detriment of other industries.

| The ship Prins

Carl: Pehr Osbeck, Dagbok

öfver

en

ostindisk

rese

åren

1750,

1751,

1752:

Med

anmärkningar

uti

naturkunnigheten, främmande folks språk, seder,

hushållning, m.m., Stockholm: Grefing, 1757; repr.

Stockholm: Rediviva, 1969, p. 4. The ship Citizen: William C. Hunter, The ‘fan kwae’ at Canton before treaty days, 1825–1844, 2nd edn Shanghai: Kelly and Walsh, 1911 (orig. 1882), repr. 1965, 1970, p. 2. Mercury: C. F. Liljevalch, Chinas handel, industri og statsförfattning, jemte underrättelser om chinesernes folkbildning, seder och bruk . . . , Stockholm: Joh. Beckman, 1848, p. 117. |

Numerous foreign ships came to China with Mexican silver

dollars as their only cargo, and sailed home with a cargo of tea. If it

was possible to find some Western products that the Chinese would buy,

the ships’ capacity would be better utilized and the profit much

greater. A number of commodities were tried, among them lead, mercury,

and iron. Two random examples: in 1750 the Swedish ship Prins Carl sailed from Gothenburg

with a cargo of lead and some textiles, and in 1824 the American ship Citizen sailed from New York with a

cargo of ‘350,000 Spanish dollars in kegs . . . , furs,

lead, bar and scrap iron, and quicksilver’.

In 1847 the Swedish commercial attaché C. F. Liljevalch

reported that cheap imports had so depressed the price of mercury in

China that domestic production had completely stopped. In the following

we shall see a similar effect on the Chinese iron industry.

|

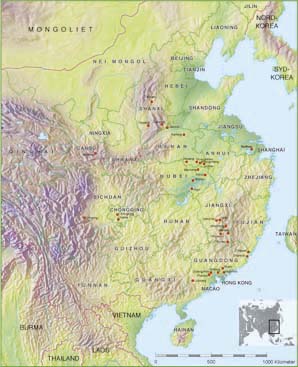

| Map of eastern China, with all place-names mentioned on the web-site. |

The final solution to the Western merchants’ problem turned

out to be opium. A triangular trade developed: textiles and other

industrial products from England to the English colonies in India,

opium from India to China, and tea from China to England. There was a

similar American trade with Turkish opium to China.

Foreign and Chinese merchants used the same effective sales

techniques as modern narcotics pushers, and before long opium addiction

had become a serious social problem in China. With the drug abuse came

new economic problems, for now silver flowed in the opposite direction,

out of the country. Corrupt officials made the prohibition of opium

difficult to enforce, and an honest official’s attempt to enforce it

led to the infamous Opium War with England, 1840–42. This was the start

of a serious decline for the Chinese state, for it soon became apparent

that the Chinese military did not have a chance against modern military

powers.

Successive Chinese governments in the next hundred years made

great efforts to acquire modern technologies from the West –

telegraphy,

railroads, steamships, artillery, and much more – but were constantly

under pressure from internal unrest and external aggression. The Qing

dynasty lost much of its freedom of action with the ‘Unequal Treaties’

which it was forced to accept.

The Qing dynasty fell in 1912. The Republic of China,

established by Sun Yat-sen, was not strong enough to hold the country

together, and local warlords took power in large parts of China. Japan

had de facto occupied

Manchuria from about 1905, and invaded North China in 1937. After the

end of World War II the civil war continued, and ended in Communist

victory in 1949.

The strong central government established by the Communists

brought

peace, reconstruction, and modernization, and China has had many

successes in the latter half of the 20th century. But the same strong

power has made possible some ideologically based dispositions which

were highly counter-productive. The Great Proletarian Cultural

Revolution, 1966–76, now called ‘the ten lost years’, is the best known

example. Less well known is the ‘Great Leap

Forward’, 1958–60, which

included forced collectivization and was followed by what has been

called ‘the worst famine in the history of mankind’, in which millions

of people died of starvation.

China today appears to be in a period of rising prosperity

which can lead to a restoration of the national greatness of former

times. Time will tell whether the dynastic cycle continues to operate.

Click on any image to see it enlarged.